Para leer en español peruano, haga click aquí.

An analysis of Peru’s unprecedented shift towards leftist populism by an American-Peruvian writer who has been working with rural communities across the Andes for the past decade. Stanziano has been on the ground in Peru since the outset of the pandemic, voting in its election and observing events in real-time.

Peru went to the presidential polls on April 11, 2021 with a field of 18 candidates. The election came on the heels of four presidents in the past five years, one of the highest death rates of coronavirus globally and an economy that shrank 12% in 2020, second in Latin America to only Venezuela – a global pariah and quasi-failed state. To the surprise of many, the candidate who took in the most votes was Pedro Castillo, a farmer, teacher, local politician and Marxist from Cajamarca, a rural province in northern Peru. Castillo only garnered 18% of the votes with the runner-up Keiko Fujimori getting 14%. The two will compete in a run-off in June.

Fujimori is the heir of an autocratic and corrupt political dynasty who recently spent a year in jail ahead of a trial which could see her serve 30 years for money laundering and leading a criminal enterprise. She has been the torchbearer for two decades of “Popular Force” a powerful political party, started by her ex-president father, Alberto Fujimori, who has been jailed on human rights convictions for a decade. Alberto and the party he founded made significant inroads in the provinces as part of his campaign to defeat the Shining Path, a Marxist insurgency that raged terror across the country in the 1980s and 1990s. Keiko lost by a sliver in the last two presidential run-offs in 2011 and 2016. While leading congress, she also played a central role in the ousting of recent presidents. She is generally accepted as being the most hated politician in the country, yet she still boasts a dedicated base who see her as the heir to the movement that saved Peru from collapse. Many Peruvians who are downright terrified of a Castillo victory will surely tolerate voting for Keiko as the least bad candidate in their eyes – a recurring theme in Peruvian elections.

On the other hand, many Peruvians had never heard of Castillo before his victory, his most notable achievement being leading a teacher strike in 2017. He forcefully preaches class warfare between the rural poor and urban rich, explicitly promoting the expropriation of private industry and redistribution of its wealth. In interviews, he’s displayed poor understanding of civic and economic activities, for example getting confused between the difference of total revenue a business generates versus what the business has left over in profit after it pays for goods and services. Where Peru is going from here no one knows, but what is sure is that the country’s divisions along a socio-economic and geographic chasm are only deepening.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

Keiko Fujimori on campaign in Peru. (Photo: Diario Angamos)

Inequalities between rural and urban Peru

For much of the first two decades of the 21st century, Peru was known as the Inca tiger among economists, riding a wave of commodity booms and fiscal discipline that cut poverty in half. Lima the coastal capital of 11 million is home to roughly one third of the country’s population. Its leaders are often resented by those in the provinces as “centralists”, who are out of touch with the realities of more traditional, agricultural communities in the hinterlands. This is nothing new. The early seeds of the nation state of Peru were sown with Lima’s founding in 1535. The city’s walls separated the Spanish-descended class from the indigenous and mestizo classes who supported Lima with labor and lives.

Most Limeños spend very little time outside of the city… Unless you include the city’s business and political elite who enjoy frequent escapes to second and third homes in growing beach and mountain communities that are walled off from their rural underclass neighbors. It’s a challenge for urban Peruvians to understand the daily realities for millions of farmers on terraced hillsides across the Andes (not to mention the 700,000 or so Quechua speaking immigrants from the countryside, who cling to dry hillside in shantytowns around the capital city). By the same token, provincial Peruvians don’t understand what it's like driving an SUV in the palm tree laden avenues of Lima. The country continues to struggle in building a common national identity between its fast-changing urban centers and a rural population which resents the continuing vestiges of colonialism.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

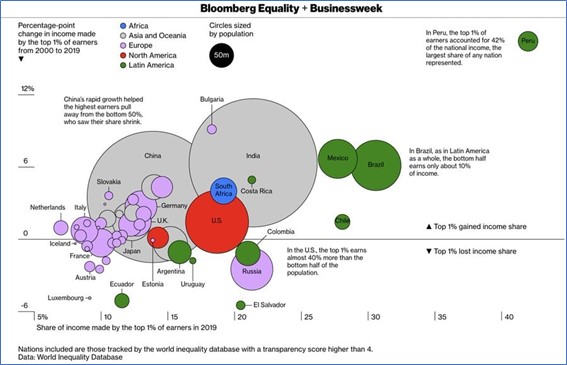

Peru is arguably the most unequal country in the world in regards to income equality. (Graphic: Bloomberg)

A few years ago, in an attempt to record the socio-economic history of Peru, your correspondent and his team of humans and llamas walked more than 2,000 miles from Peru’s northern border to its southern. It took us 10 days to walk the 200+ miles through Castillo’s base province of Cajamarca alone, moving from village to village on ancient trails, capturing daily life through writings and photography.

There exists in Peru a base of power that is not conferred by elections, but instead by older, more patriarchal Andean forms of community that are not based on municipal functions like mayors. The more remote the community, the more indigenous its organization. These structures become more hybridized and interlaced with modern civic institutions as villages grow into urban landscapes. In medium sized towns, it’s common to have a community “president” addressing more quotidian matters, alongside an elected “mayor” who would handle the management of infrastructure and tax collection.

The “Ronderos” – men from the community who oversee security and basic order – are part of this power base. It was Alberto Fujimori’s arming of these local Ronderos across Peru which eventually gave the central government the grass roots allies needed to turn the tide against the Shining Path in the early 1990s. My team and I had to submit to constant inspection from these Ronderos as we walked from village to village across Peru. Castillo is a self-proclaimed Rondero, a proponent of this more indigenous, patriarchal form of power that has always existed in the Andes and is now being used as a narrative to win the presidency. The first and only indigenous president of Peru was Alejandro Toledo – although by early adulthood he had left rural Peru and was in San Francisco, California earning a PhD. Today he’s resisting extradition for corruption at his home near Stanford. In contrast, Castillo was feeding his pigs the morning of the election and rode his horse to his polling place in rural Peru. His rise is unprecedented in Peru and is similar to, say, the rise of Evo Morales in neighboring Bolivia.

Section Type: standardWidthImageS

Pedro Castillo heading to the polls in Peru's first round of elections. (Photo: Reuters)

Pandemic and geopolitics

What few observers seem to realize is that the real takeaway from Castillo’s surprise victory and popularity is a massive political shift in rural Peru that was spawned by the global pandemic. The lockdown that began on March 15, 2020, meant that most of the country’s jobs disappeared overnight in an economy that is 70% informal. It caused a mass exodus from Lima of provincial immigrants who could no longer make a living and who took to their feet, walking hundreds and sometimes thousands of miles to their native regions after public transportation was halted across the country for months. Peru went back to its roots literally and figuratively, with many relying on the traditional support networks of family, agriculture, and native community once again.

Were Peru to vote Castillo into office in June, they would be aligning themselves more closely with populist and Marxist governments in Venezuela and Cuba. This would ultimately mean increased economic and political ties to China. It could even have the potential to alter the ongoing posturing for power in the Asia Pacific theater. Peru is a large, commodity-rich country, and a key stopping point within the Asia Pacific. It has historically had strong ties to the US, but China is making significant inroads in the country through investment in mining and infrastructure. Russia, which has a long history of getting involved with leftist movements in Latin America, might also see aligning with Peru as an opportunity to challenge US dominance.

There is much at stake in this year’s election. Questions and conspiracies abound on whether the congress, the military, or even a popular revolt might remove whoever enters the presidential palace, as has been the case with recent presidents. Castillo’s opponents accuse him and his political mentor of being vestiges of terrorism. They trace his rise back to agreements that allowed the Shining Path to transition from bombs to politics in the mid-1990s, in the process walking Peru off the ledge of civil and economic collapse. Keiko Fujimori’s strong-arm approach will shape a narrative that depicts the election as a battle, once again, in which Popular Force will save Peru from Marxist terrorists.

A repeat of history

From those who favor open markets to believers in leftist populism with an Andean flair, no Peruvian would deny that their political system is broken. The ravages of the pandemic and the ensuing economic desperation of rural populations mean that Peruvians may be more vulnerable than they have in a long time to fantastical promises like Castillo’s. And whether Castillo becomes president or not, his ideologies risk growing and festering among the Peruvian underclasses who increasingly see the economic and political elite in Lima as morally and economically corrupt.

It has only been twenty-five years since the bombs stopped in Peru’s last battle between radicalized political ideologies. The only way to build consensus in such a fractured and diverse country is to build a common future and a common idea of Peruvian identity. Rural Peruvians will have more opportunity if their country has open markets and a thriving capital. Urban Peruvians and especially regional governments need to support education, health, and economic development of the countryside, so it can reach its full potential and leverage the country’s vast natural and human resources.

For now, Limeños continue to act shocked that a farmer from rural Peru could have won the first round of a presidential election. The fact that it's a surprise is proof of just how out of touch they are with the rest of the country. At the same time millions of rural Peruvians celebrate a candidate who was a natural choice in their traditional, Ronderoesque version of the world. The fact that they believe that class warfare and fundamentalist Marxism is hope for the future is proof of just how left behind they really are.

Section Type: backgroundOnly

About the author: Nick Stanziano co-founded SA Expeditions and serves as its CEO. Originally from California and a nationalized citizen of Peru for a decade, he straddles two worlds. Nick has a BA in Global Studies from the University of California and a trans-global MBA from Saint Mary’s College of California. Nick believes that tourism companies of the future increasingly have a responsibility to accurately portray the human struggles of the countries to which they bring travelers.

You can see his entire portfolio of articles here or read his recently published e-book, that followed his 3,000 mile journey across Peru by foot on the Great Inca Trail, also known as the Qhapaq Ñan.

All images used in this blog are republished in the public interest. While every effort has been made to credit the photographers responsible for documenting this important moment in Peru’s history, interested parties should feel free to contact us directly. Title photo: Francisco Vigo/EPA

South America

South America South America

South America